Discover Australia’s newest World Heritage Site

Australia’s newest World Heritage Site reveals the 6,600-year-old ingenuity of the Gunditjmara people. By Natasha Dragun

Budj Bim Cultural Landscape Tourism, Victoria © Tourism Australia

It’s early morning when I arrive at Budj Bim Cultural Landscape, and a heavy mist blankets the countryside like a protective cloak. Dew dapples spider webs that resemble intricate lacework, clinging to spindly gums and tufts of reeds that appear amid sculptural lava rock as the sun burns through the fog. It’s impossibly quiet; an insanely beautiful setting. I can feel my pulse slowing.

Budj Bim Cultural Landscape Tourism, Victoria © Budj Bim Cultural Landscape Tourism

I’m on Gunditjmara Country in southwest Victoria, at the end of the Great Ocean Road. And I’m privileged to be visiting Australia’s newest World Heritage Site – one of 20 across the country, and the only one recognised for its Aboriginal cultural values. “Welcome to a very special place,” says my Gunditjmara guide for Budj Bim Cultural Landscape Tourism, which offers guided cultural tours of the site.

Guide points out over Tae Rak (Lake Condah), Budj Bim Cultural Landscape Tourism, Victoria © Tourism Australia

He's showing me around the dramatic volcanic landscape, which comprises three components: Budj Bim National Park, which is cooperatively managed by Gunditjmara Traditional Owners and Parks Victoria and includes the long-extinct volcano formerly known as Mt Eccles, the source of the Tyrendarra lava flow; Kurtonitj, which means ‘crossing place’; and the ceremonial wetlands of Tyrendarra, all of which show extensive evidence of the largest, most complex and oldest-known aquaculture system in the world.

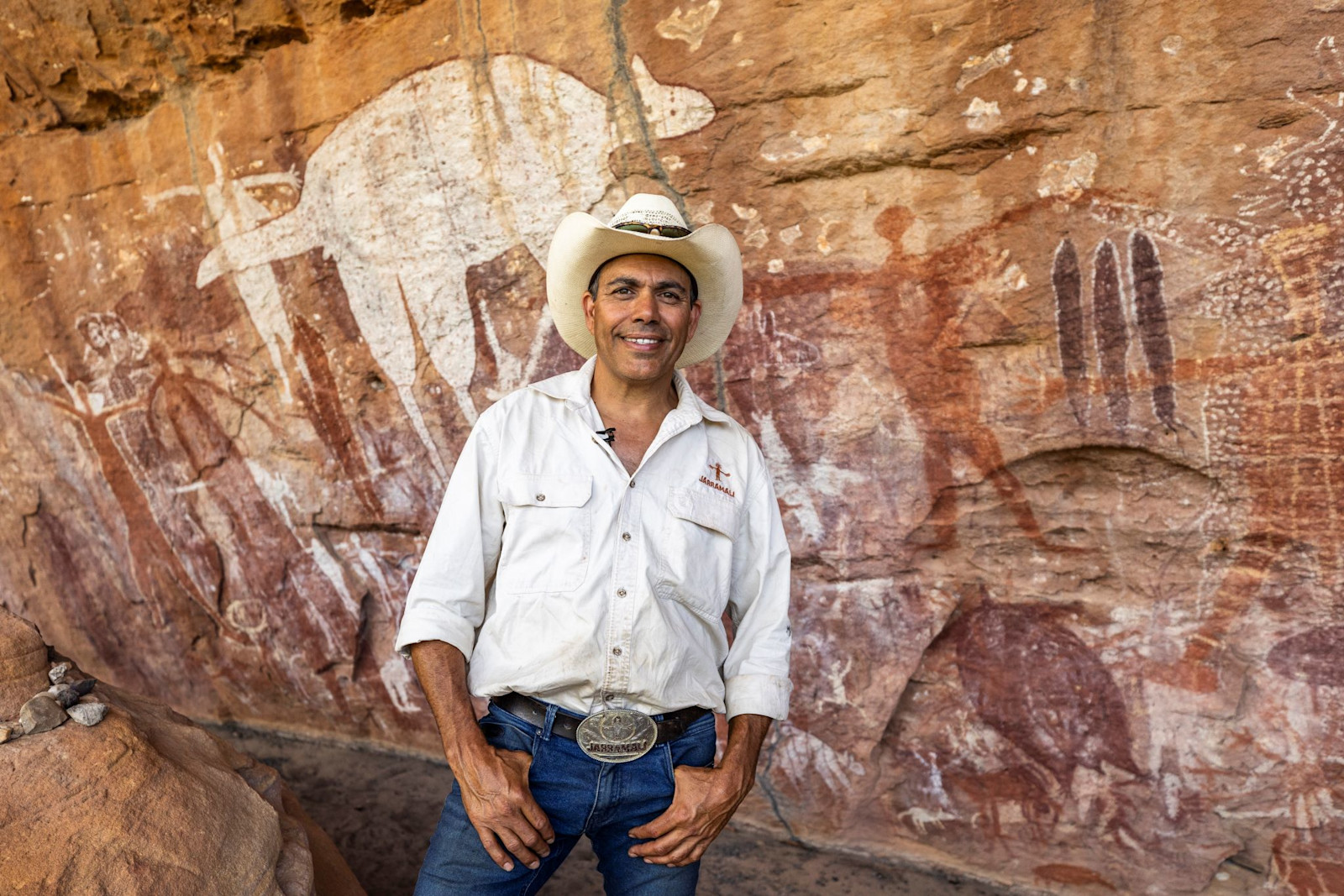

Guide gives a cultural talk, Budj Bim Cultural Landscape Tourism, Victoria © Tourism Australia

My guide tells me that the Gunditjmara people used the volcanic rock here to manage water flows from Lake Condah to exploit kooyang (eels) as a food source. “They constructed an advanced system of channels and weirs to manipulate water flows to trap and farm migrating eels and fish for food. They did all this more than 6,600 years ago. “Pretty amazing, hey?”

Aerial view of Budj Bim Cultural Landscape © Tourism Australia

Today, the aquaculture systems are maintained by a team of Budj Bim rangers, who work in revegetation, feral animal control, weed control and give tours to visitors. The landscape is fragile, so we explore on a series of raised boardwalks, my guide pointing out the smoking trees where eels were prepared for eating or trade, and the stone huts where people lived near their aquaculture sites – there are more than 100 of them. “For a long time, people thought all Aboriginal communities were nomadic,” says my guide. “These huts show we put down roots as a community and that we had strong farming practices.”

Tae Rak Cafe © Tourism Australia

It's almost noon, and the smell of smoked eel wafts over the boardwalks. My guide leads me back to the architect-designed, off-grid Tae Rak Aquaculture Centre, carved from red and spotted gum, blue and volcanic stone. The source of that delicious aroma is the on-site café, where chefs prepare eel tasting plates (think smoked kooyang, kooyang arancini balls, kooyang pate) and other dishes infused with native ingredients like bush pepper and lemon myrtle. It’s a tasty end to the tour, and like Budj Bim in a mouthful.

Tae Rak Cafe © Budj Bim Cultural Landscape Tourism